Remember when we did Grand Gettysburg back in August 2021? The biggest civilian online live Kriegsspiel run so far, with 34 players and about 50 participants in total. Those who participated remember it fondly, what an experience. You’ll find several recordings under videos.

That was of course not the first game we played on Damon’s beautiful map. We did several test games of Alex’s Brigade System which we used back in the day, and the teams ran drills to prepare for the big event.

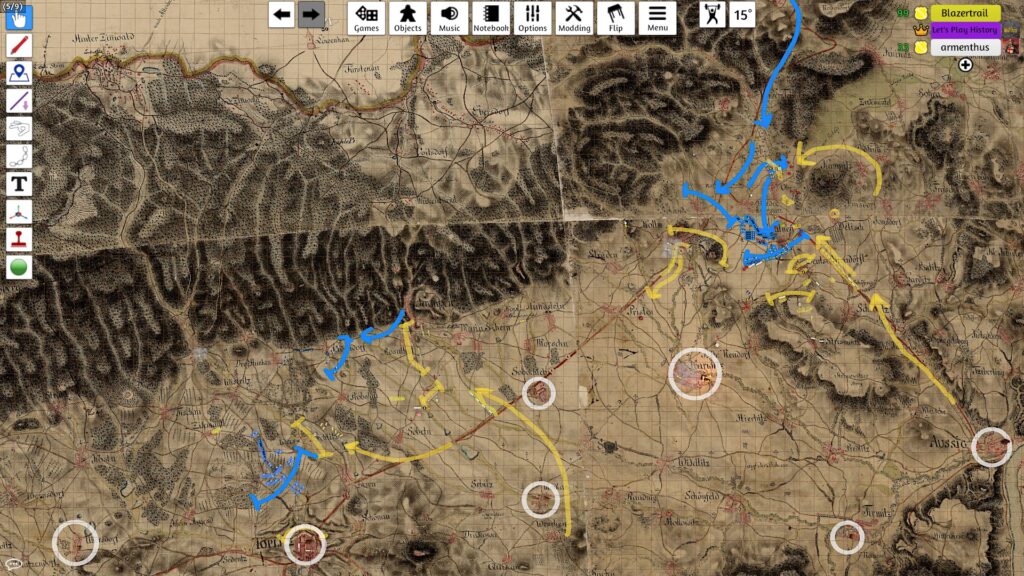

Here are some reports of a 3v3 corps-on-corps game we played on 26 June 2021.

This is how Marshall’s experienced the battle.

McLaws - A Fresh Look at a Mistreated Hero

Without dispute, historians agree the Battle of Gettysburg, which took place on June 26, 1863, was a decisive Union victory. The action in that battle was sufficient to knock an entire Confederate corps out of effective action, thereby allowing General George Meade to defeat Lee soon afterwards and crush the Confederacy’s chances of winning the war. For this reason, the battle is often scrutinized. In the words of Shelby Foote, “Every southern schoolboy has imagined himself in the shoes of a soldier in Barksdale’s Brigade… It is 3’o-clock, the hottest part of the day, and General McLaws, his brow dripping with sweat as he rides up to Barksdale, salutes and signals with a gesture of his hand. The fateful order is given.”

General McLaws’ actions are the subject of great scrutiny because it was the tardiness of his actions that appears to have cost the Confederacy the battle, and ultimately the war. However, modern historians, studying the primary sources of the period have widely come to see McLaws in a new light. The emerging consensus is that McLaws was thrust into a critical, yet impossible position from the break of day, and in spite of this circumstance, actually came much closer to winning than most historians were willing to admit.

The data for this conclusions comes from a wide variety of sources, including a wider range of primary sources disregarded in the aftermath of the battle. Reports from junior officers, as well as many letters from enlisted personnel on both sides of the battle reveal a different account of what actually happened that day.

In the popular history that until recently was taught in schools, McLaws is painted as a ponderous commander, taking time to make overly-cautious decisions, moving slowly, marching, countermarching, then only committing to the attack once General Longstreet personally begged him to attack. Even then, McLaws went piecemeal and slowly, leaving Barksdale’s brigade to bear the brunt of the fighting until it was spent, then sending in Kershaw and Semmes when he could no longer find an excuse to delay.

Needless to say, this history is both vindictive and unkind, not to mention, an a-historical myth. Justice, and the historic record demand correction, and General McLaws deserves satisfaction, even if posthumously awarded some fifteen decades after the fact.

The most bruising criticisms of McLaws are not supported by any primary source. Not even General Longstreet wrote anything remarkably close to the tale that would emerge from the scapegoating that would take place after the war. On the contrary, even McLaws’ enemies noted that his attack was frightening and effective. The historic accounts plainly concede that McLaws threw back the Union forces, across the Emmitsburg Road, making his attack the most successful action of the day for the Confederates.

Yet, as indisputable as his success was, it is also indisputable that he was the last of the Confederate divisions to enter the battle. His defense rests on the question of whether or not his tardiness is justifiable.

On the evening of June 25, McLaws was ordered to establish camp along the east banks of Willoughby Run. This was a sensible deployment, since the run provided fresh water and shade for the men on the early evening of the 25th. Of all the dispositions for all the forces that would be engaged the following day, McLaws’ encampment was the most comfortable and well-selected.

McLaws attended a council of war with General Longstreet after dark on June 25. At the meeting, Longstreet shared intelligence gathered by scouts that Union forces were approaching Gettysburg and that his corps was ordered to attack and drive them away from the strategic crossroads at Gettysburg.

Longsteet established the route of march to the battle and directed McLaws to move north, along the banks of Willoughby Run, to cover the eastern flank of the corps. Notes from the meeting clearly indicate that McLaws pointed out to his peers that the route would be intermittently wooded and would require some cross-country movement when trails were unavailable, including the dismantling of fences that could impede the progress of the division. Longstreet acknowledged this fact, but affirmed he preferred for McLaws to take the more difficult route because It screened his forces from possible observation to the south, and that “With Barksdale in the lead,” his men were the most capable in the corps.

McLaws registered no further concern and on the morning of June 26, stepped off thirty minutes early, to make allowance for the difficulty of the march. Had the battle been joined by 9:00 or even 10:00 AM, McLaws’ early movement would have placed him in a deadly position relative to the rest of his corps, but the battle was not joined until 11 AM, when his head start had eroded to “an even disposition,” relative to the rest of his corps.

As his division approached Gettysburg, McLaws became increasingly concerned about how quiet the situation was, even though it was nearly noon. He had not received any communication from the rest of the corps, and he sought to check his position relative to the other divisions. To accomplish this, McLaws ordered his two leading brigades to move east, along a trail that connected to the Emmitsburg Road. However, in the interest of keeping the corps covered from the west, and in keeping all his forces moving with the division, McLaws ordered Semmes’ brigade to continue following Willoughby Run. He directed Semmes to turn towards the Emmitsburg Road on another trail, called the “Pfitzer Road,” a half-mile further.

McLaws rode ahead to Seminary Ridge, and took a quick measure of the situation. Upon arrival however, he did not spot the Union forces that were closing to contact along Emmitsburg Road. He did look for tham as the accounts of his subordinates affirm, but neither he, nor any member of his staff, saw the blue column approaching from the north.

This is one of the great mysteries of the day, since it is a fact the battle was joined just minutes later. Only recently have experts attempted to study this mystery and the conclusion appears to be that McLaws’ position, and the angle of the Union forces, still moving in column, offered a narrow target for visual observation. It is also likely the head of the Union column was probably obscured by trees or blended in with more distant objects. In any case, it is certain that Mclaws did not see the Union forces, nor did any member of his staff, which exonerates him from accusations of poor eyesight, laziness, or mistake.

With the Union undetected and the battle not yet joined, McLaws ordered his men to return to their original plan, but with some modifications which would allow him to react quickly to any sudded appearance of Union troops. His first two brigades were to follow a trail along the crest of Seminary Ridge. He also ordered his batteries to move through open country when trails were unavailable. The order, distinctly catalogued after 11:00 AM, was issued to prevent the guns from being “slowed or busted by terrain.”

The nature of the terrain over which McLaws was asked to march was far from easy. Fences were frequent, and engineers were required at the head of the column to remove split-rails and other obstacles. It was a credit to those brave pioneers that McLaws’ men were able to move with the speed they achieved. In fact, judging from accounts of the period of units moving along open roads, comparisons surprisingly suggest that McLaws’ men kept up virtually the same pace as a unit moving by road.

McLaws himself urged the men forward so much so that no less than three letters written by enlisted men under his command refer to the pace of the march as “swift,” and “rapid,” and in the most critical account, “tough.” McLaws himself explained he was sensitive to the position of his force relative to that of his comrades, and he wanted to be “near enough to rapidly render support.”

However, despite his best intentions, McLaws’ plan to be near at hand when battle was joined was soon thwarted by the ground across which he was moving. The wooded line of Seminary Ridge was such that McLaws was compelled to veer back to the west, closer to Willoughby Run. However, the venerable commander did not despair over this circumstance, instead pointing out to an aide that the shift back to the west would also conceal his movement, should the enemy emerge.

Just minutes after issuing these orders however, McLaws was alerted by the sound of booming artillery. Contact was made. He immediately revised his orders, and directed Barksdale and Kershaw to move immediately to support the rest of the corps. However, he ordered that Semmes continue his overland march with the intention of outflanking the enemy. His orders were based on a best guess of the enemy’s likely position.

At this point, events happened quickly. The historical record is confused on all sides.

McLaws gave a remarkable order, one that is often overlooked. He sent Barksdale’s men forward at quick time. This order, rarely mentioned in the secondary sources, but found in his after action reports and confirmed by Barksdale himself, suggests McLaws was far from the dawdling fool he was accused of being after the war.

While executing this order, McLaws was presented with new orders. His call to battle was premature, and he was about to emerge behind friendly lines. His orders were to flank around to the north, as he originally intended. McLaws obeyed.

As McLaws obeyed these new orders, Union forces sprung their trap to the east, beyond McLaws’ sight. They smashed into Longstreet’s right flank and sent his men on the Emmitsburg Road reeling. A dispatch was sent to McLaws, urging him to enter the fight. This report was the first indication that something was wrong.

Once again, McLaws revised his plan to execute a wide flak march, and drove his forces straight into battle. He sent Barksdale’s men in ahead, knowing he could rely on them to drive back any opposition.

Barskdale did exactly that with Kershaw and Semmes close behind.

However, Barksdale’s men smashed the Union forces, but were forced to contend with far greater numbers. Once he observed the odds facing Barksdale, McLaws gave the order for Kershaw to relieve his men in line, and replace his brigade. Semmes was ordered into the attack. This would give Barksdale time to reform and resupply so he could become combat-effective once again.

Kershaw and Semmes continued fighting for the next hour, before Barksdale’s brigade resupplied and reformed. Once ready, McLaws ordered Barskdale to take position on his right flank. By this time, the rest of his corps had retreated back to the south, leaving McLaws unsupported, fighting by himself.

McLaws compensated for this by ordering his brigade to continue pushing forward. The intensity of the offensive was so tremendous that at one point, Semmes’ brigade found itself firing on Union cavalry troopers who had already retreated.

Still, the Union forces opposing McLaws fared badly, and were soon forced back across Emmitsburg Road.

As Barksdale formed on the right, a desperate Union charge advanced through the smoke. Barksdale countercharged at once, and swiftly repulsed the Union men.

After this violent clash, in which the Union yielded to Barksdale, a lull in the battle developed. It was than that McLaws was ordered to withdraw. With reluctance, he obeyed, thus ending the fighting on June 26.

What should be clear from these records is that McLaws attempted to enter the fight on more than one occasion. He was forced to return to his original plan each time. Regardless of the setbacks, his force was the only division that succeeded in repulsing the Union. His initial position, and his marching orders came from General Longstreet, and he cannot be faulted for obeying orders.

Ultimately, a close examination of the facts reveals that McLaws attempted to enter the fight and was compelled to wait and flank the enemy until the battle was largely decided, well out of his sight. Even then, McLaws attacked and did so with such ferocious skill that the Union was hapless before him.

The historic record is overdue for correction. Perhaps this analysis of the battle will posthumously exonerate McLaws and permit him to take his rightful place among the heroes of the Civil War.

Join our Discord server and become part of a growing community of over 750 members from all around the globe.

Get in touch either on Discord or via e-mail, leave us some feedback or suggestions or ask us anything about Kriegsspiel.

The IKS is commited to ensure inclusiveness and diversity within the community and stands against discrimination and harassment.